My ride drops me off at the border where I plan to begin a northbound journey. But after they drive off, I turn around and walk south instead. Probably because I can see an obvious trail heading in that direction, while the one going in my intended direction is elusive from my vantage point. It’s surely somewhere ahead, but it’s out of sight and the thought of it is foreboding.

Later that afternoon, I stop to catch my breath. I’ve reached a rare clearing with a view that validates my last hour’s grinding effort. Below, Pacific whitecaps crash into solitary basalt islands, while western gulls glide effortlessly on wind currents above. I only want to sleep.

Ominous clouds in the northern skies race southward. How long do I have before the sun is doused by heavy thunderheads and the torrent overtakes me? One, maybe two hours?

I didn’t think I’d need a parka today, and right now mine is stuffed in the bottom of my untested 90-liter Lowe Contour. I should probably dig it out, but I’m too exhausted. I maneuver to allow the load to fall from my back and into a patch of native ferns where reddish arms of new growth unfurl like snails.

The only thing I did to physically prepare myself for this was one long walk. I filled my dad’s old Himalaya frame pack with hefty river rocks wrapped in towels, then ambled, wearing that rickety pack, fifteen road miles from my house in Huntington Beach to my favorite cafe in Laguna, Fahrenheit 451, where my dad picked me up and we got cappuccinos. “The trail will get you in shape,” my dad said. “You’ll be fine.” When he asked how it went, I told him that drivers honked as I appeared inexplicably on the roadside, a few flipped me off, and a couple kids hurled chunks of tanbark at me from the backyard of their mansion. My dad nodded, completely unsurprised.

This morning I did my best to evenly distribute weight. Tried to keep the heaviest stuff, including three cans of beer and two hardcover books, towards the center of the load. I imagined I’d finish my days sipping Sierra Nevadas and reading Alan Watts. But at this point I want to jettison such luxuries. This strenuous section of the California Coastal Trail is making my burden unbearable.

I take a seat on a boulder and lift my feet from the earth. My sweaty hands pick at crystallized bits in the ancient lava and I wonder: Should I mess with my bulging heel blisters now or wait until later? Also, is there a campsite ahead? And when’s the next water source? I also wonder if there wild animals out here. I should have brought a map, or at least consulted one beforehand. I regret telling the hiker I saw an hour ago that I was good to go. Because I am not. I wish she would come along now and offer me a piece of that homemade jerky I reluctantly declined. Was it teriyaki or peppercorn? Was she even real? What a fool I am.

I’ve made a big mistake starting this hike, but what can I do now besides keep going? As much as I want to throw in the towel, I’m in the middle of nowhere and far from home. I don’t know anyone nearby who could potentially rescue me, and even if I did, the prospect of succumbing to failure overwhelms me with shame.

Backtracking might be the smartest thing to do, but I can’t bring myself to turn around. Redoing the known distance behind me frightens me more than what’s ahead. The southward pull continues, offering a bit of hope in the unknown. I have to keep going.

Still, the last thing I want to do is return my backpack to my smarting shoulders, raw with bruises and chafe. I slowly peel back my cotton shirtsleeve and crane my neck to see the damage. My flesh is warm to the touch, and as I run swollen fingers over my abraded collar I expect to feel bone. My light touch offers a moment of relief. With closed eyes I momentarily dream of all I’ve left behind and a lump grows hard in my throat.

After another look at the empty horizon, I heave my pack from the ground and onto the sitting rock. I then strain my torso to get my arms through the straps. With a grunt I deadlift the load and bend forward as I tighten the straps in the proper order as I read in Backpacker Magazine—waist belt, shoulder, chest, and load lifters. I stagger under the encumbrance, then my toes make fists to find steady purchase on a patch of soft moss.

For a moment I feel like everything is going to be OK. But then I remember I’ve never set up my tent. Which means I’ll need to stop before the sun sets or the storm hits, preferably both. I hope the guy who sold it to me was right when he said it had all its pieces, because the stakes and poles are all where he stuffed them in the tidy orange sack. Surely he knew what he was doing. I continue on the trail, and appreciate level ground for my first few strides.

Soon I’m climbing again. The single track is so steep I can touch the ground by simply reaching out in front of me. My burning calves are on the verge of cramping as the first rumble of thunder races across the sky. Then comes the downpour, for which there is no buildup. One second the forest of redwoods and box elders is bone dry, the next it’s submerged in what seems to be an ocean suddenly flipped upside down.

The storm lingers, unrelenting. After more than twelve hours on trail I’m soaked through and pickled. For the past hour I’ve been inspecting possible campsites and have declined them all. Too angled. Too small. Too exposed. Another with a massive widow maker in the old white alder above an otherwise perfect site. I think, Maybe this is how I will die. I then wonder if tears and raindrops are the same size.

I squint at a strange glow weaving through the far distance and think of the Spook Light I saw as a kid near Quapaw, Oklahoma. Legend has it the light is the ghostly lantern of seventeenth century forbidden lovers who plunged to their deaths over a perilous waterfall to escape their families’ refusal to accept their betrothal. I was maybe ten years old when I watched it bounce across the dirt road. I wanted nothing to do with it and immediately raced back into the car.

This light slices trees, moving at a faster rate than anything I’ve seen all day. When a second one follows, I think the worst—perhaps someone, someone bad, is out here hunting me. Watching for my shadows. Or maybe the lady at the rest stop yesterday wasn’t kidding when she smiled and told me not to get abducted. “By what?” I asked. “Aliens,” she said as her face hardened.

I’m suddenly aware that thoughts of self preservation have replaced my grueling pain, which makes me grateful for them.

I stand stupefied when the muddy rollercoaster dumps me onto the coastal highway. Have I been this close to a road all day? Without a second thought I exit the swampy trail and beeline towards an official looking green and yellow building. A stray sunray illuminates its peeling rooftop. Maybe I won’t have to camp after all, I say, as I float to the front door, over which is a sign that says, HOSTEL.

Inside, a shirtless man in a swimsuit writes my name in a register and directs me to the bunks. He tells me the daily Greyhound will stop out front if it’s waved down. I shelve his comment and tell him that tomorrow I’ll be back on the trail after having learned something from today’s sufferfest. He laughs, which makes me feel self conscious.

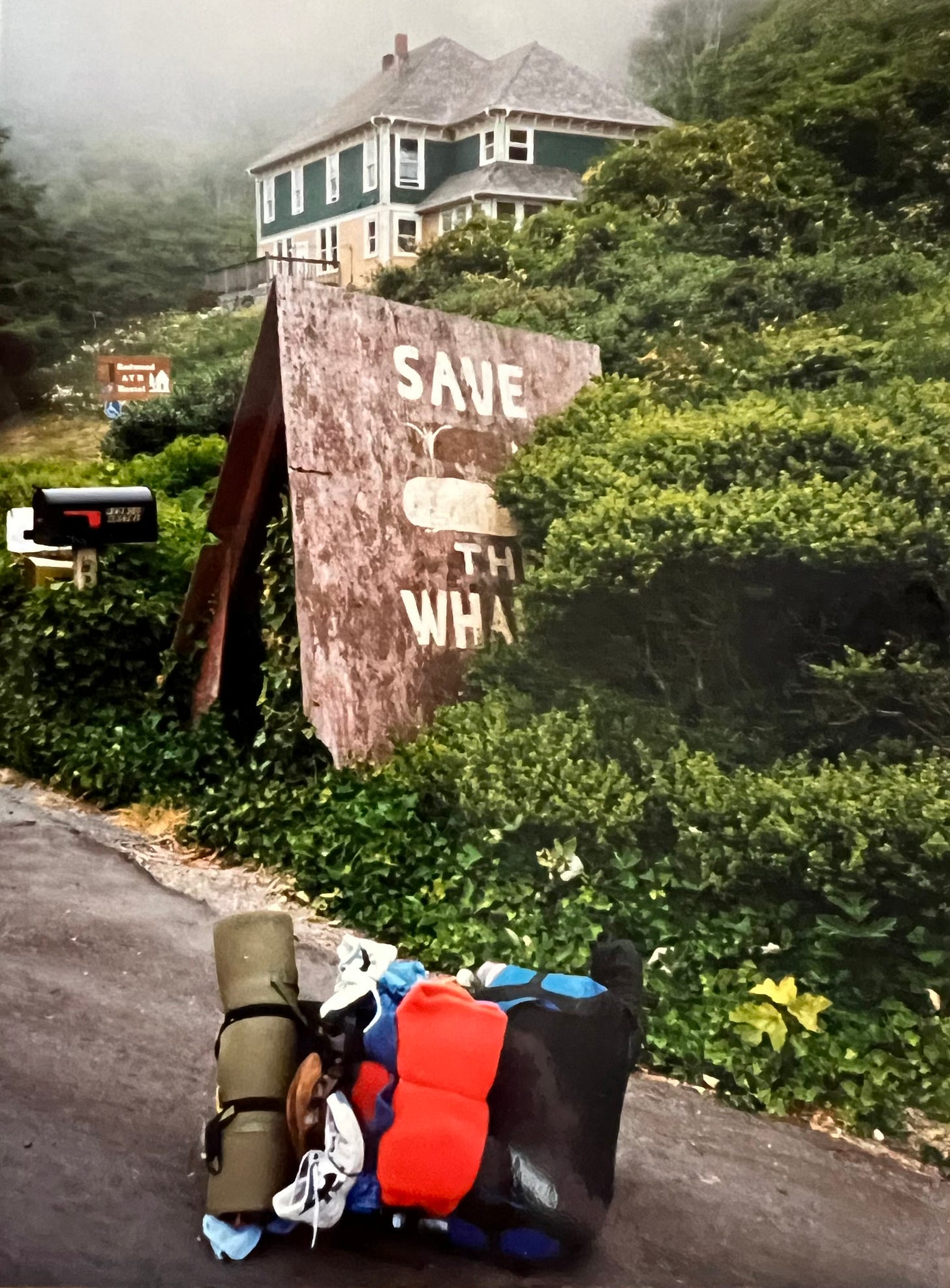

The next morning I take my time with the communal breakfast and my mandatory chore—collecting the dirty shower towels. I procrastinate until I grow bored with it and repack my gear. Then I begrudgingly don my hulking pack and can’t believe I’ve carried it this far. At the bottom of the steps I shout thanks to anyone who might hear and exit the way I arrived. The sky is blue like it’s never known a cloud. A scrub jay makes its presence known before disappearing into the high tree boughs.

I make my way to the road with plans to cross and return to the trail. But as I near the blacktop, I’m struck by a flashing reflection of the silver bus as it lumbers around a bend before vanishing again. My step turns inexplicably light as I flash across the highway to the southbound side.

The vehicle comes back into view and my first wave is hip-high and reluctant. When it’s close enough that I can hear the engine, I jump up and down, flailing my arms and body as the gear hanging from carabiners on my pack makes a kind of lumpy music. “Stop! Stop!” I shout. Its brakes squeal as it pulls to the road’s shoulder. I hobble to the passenger door as it opens to welcome me on.

The driver exits and opens the luggage hold. He then helps me remove my massive pack together we stuff it among clean suitcases and duffels. “How far have you been carrying that?” he asks. “Too far,” I say.

We board the bus and I take the first open spot. I have no idea where I’m going. But anywhere but here is fine by me.

This reminds me of an evening I spent at an AT shelter in Virginia with a novice backpacker. We held each other in high respect; I was just a college kid between semesters, but knew the ropes for trail ease, having hiked 700 miles to get to that spot.

He was 15 years older than me and had made it in the world as an investor and developer of historic landmark buildings. (His advice: stay away from New England where it's damp and "old" is at least 200 years ago; look to the southwest where it's dry and old is 100 years ago).

He had four hard back books in his pack. I supressed a laugh and said he was undoubtedly the owner of the largest AT library for many miles around.

I can relate to the balance of not knowing much (how to set up the tent) and knowing just enough (widow maker branch bad). Maybe not the specifics of those two situations but just in general. Also can’t believe the Lost Coast solo was your first backpacking endeavor!